At the HSE KSA 2025 conference in Riyadh, Larry Wilson, founder of SafeSmart International and a globally recognised authority on serious injury and fatality (SIF) prevention, challenged one of the most deeply ingrained phrases in workplace and public safety culture: “Be careful.”

“It doesn’t matter what language,” Wilson told delegates. “It’s been used by parents for thousands and thousands and thousands of years.” Yet despite its universality, he argued, it has consistently failed to prevent injuries — both at home and at work.

Wilson illustrated the paradox with a personal anecdote from early in his career. Visiting an oil company that proudly showcased its comprehensive safety management system, he recalled being handed a red binder containing “all of the rules, procedures and the different 23 elements in their health and safety management system.” Despite this, the safety professional stressed that employees still needed to be told to be careful.

“When I asked, ‘How do you teach them how to be careful?’ he said, ‘We tell them they need to be careful,’” Wilson said. “We all know it didn’t work for us. So why are we saying the same things to our children? Why are we saying the same things to our workers?”

To answer that question, Wilson led the audience through what he described as a “personal risk pyramid” — an exercise he has now conducted with more than five million people across 76 countries. While organisations tend to focus on recordable injuries and lost-time incidents, Wilson urged delegates to consider the thousands of minor, unreported injuries that occur over a lifetime: cuts, bruises, bumps and scrapes.

“Most little kids have got somewhere between ten and 20 visible cuts, bruises, bumps and scrapes on them per week,” he said. “That’s 5,000 by the time we’re twelve.” When viewed this way, the traditional belief that serious injuries are largely the result of bad luck begins to fall apart.

“If it was ten to one, you could say random chance or luck,” Wilson explained. “At a thousand to one, we all know we should have been looking for an assignable cause.”

That assignable cause, he argued, is not equipment failure or the actions of others — factors that account for only a small percentage of serious injuries — but the individual themselves, particularly when their attention is compromised. “Over 90% of the serious injuries… it wasn’t the equipment or the other guy that was the unexpected event,” Wilson said.

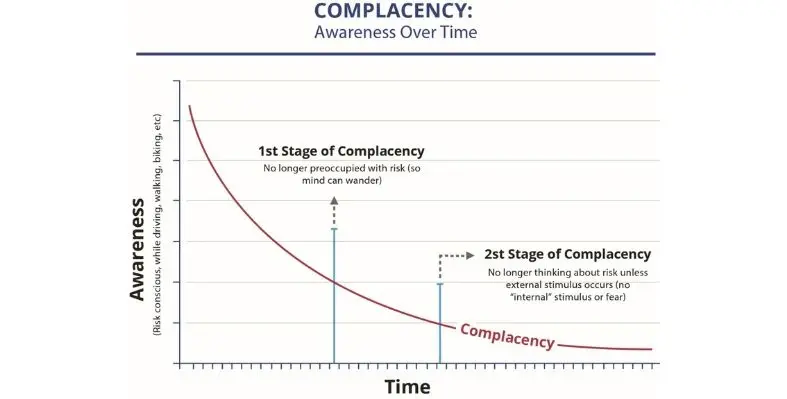

The crucial distinction, however, is why people make these errors. According to Wilson, the problem is not carelessness but neurobiology. “To always be thinking about safety is neurologically impossible,” he said. As people become competent at a task, their brains automatically shift into what he described as the first stage of complacency — a state in which the mind begins to wander without conscious permission.

This process is driven by the reticular activating system, which filters out familiar stimuli to conserve energy. “When people become competent, they will also become complacent,” Wilson noted. “We need competence. But with the competence will come complacency.”

This is where Wilson’s concept of “eyes on task” becomes critical. While people may be mentally distracted, maintaining visual attention allows them to benefit from their reflexes — a powerful but often overlooked protective factor. “If you don’t see it or you don’t see it coming, you’re not going to get the benefit of your reflexes,” he warned. “And for that moment you will be defenceless. And that is when the majority of serious injuries and fatalities occur.”

Wilson emphasised that many fatal incidents do not happen during high-risk tasks but during routine, mid-level activities where vigilance is lowest. “The majority of serious injuries and fatalities occur in the middle,” he said, calling this reality “counterintuitive” but statistically well established.

Rather than telling people to “be careful” or “think safety,” Wilson advocated for teaching specific, observable habits that keep eyes on task. These include testing footing or grip before committing weight, moving eyes before hands or feet, and checking line-of-fire hazards. “Those are actually doable,” he said. “It’s almost impossible to ask people to work on five things at once. So pick the one that would help you personally the most.”

Equally important is learning to self-trigger during moments of rushing, frustration or fatigue — conditions that can cause what Wilson described as an “amygdala hijack,” where stress hormones override rational thought. “As soon as you realise you’re rushing or frustrated or tired, you’ve got to quickly think: eyes, mind, line of fire, balance, traction, grip,” he said.

Wilson concluded with a clear call for change. “We need to change ‘be careful’ to ‘keep your eyes on task,’” he told delegates. “And we need to teach people how to self-trigger on the active states so they don’t make a critical error in the moment.”

For safety leaders seeking to reduce serious injuries, Wilson’s message was unequivocal: effective prevention lies not in slogans or reminders, but in aligning safety systems with how the human brain actually works.